History Of Comics

COMICS IN THE ERA OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

By Joshua H. Stulman

Black characters in comics have existed since the very foundation of the industry. However, the depictions of black characters in comics have grown along with pop culture. Black characters originally served two purposes in golden age comics. The first purpose was as comic relief (and many times racial comedic relief). These caricatures were heavily based on minstrel and Sambo imagery that was still popular at the time. The second use of black characters in comics were in relation to the imagery of Africa and “nativism”. However in the aftermath of World War II, the portrayal of black characters in the comic industry began to evolve through the years beginning in the early 1950’s.

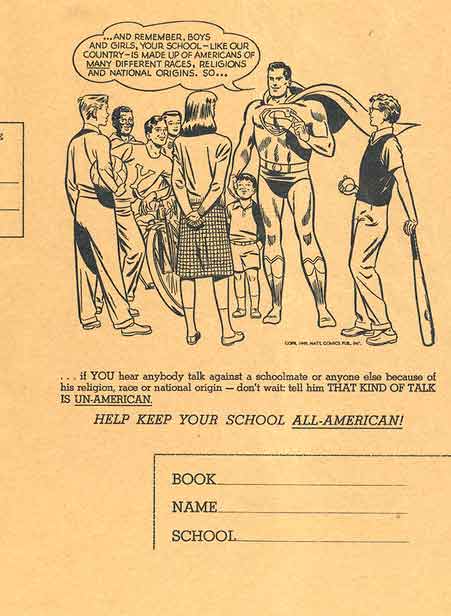

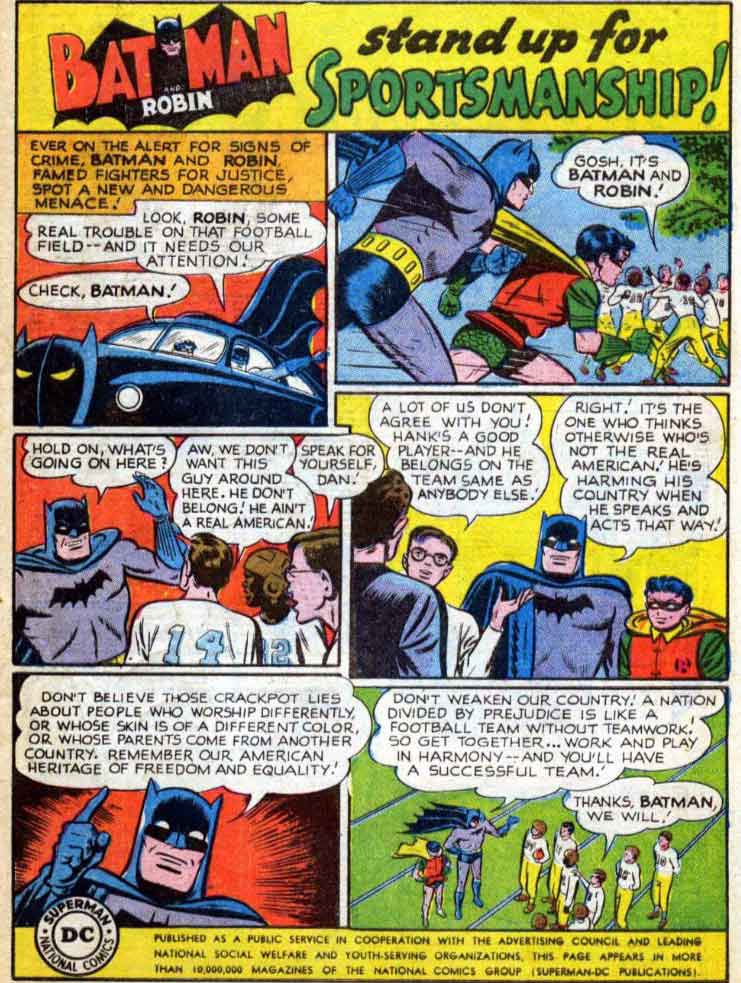

As the Civil Rights movement was growing in the 1950’s, the comic industry was already embracing the fight against racial inequality. In 1949, DC Comics used Superman’s popularity to help raise awareness of racial and religious discrimination. In conjunction with the Institute for American Democracy, DC Comics produced paper book covers for school text books with an illustration of Superman speaking to a group of school kids. Artist, Wayne Boring, included a young black boy in the crowd. Here, Superman addresses the group by stating that anyone who speaks badly of any student because of their religion, race or national origin, was un-American. A year later, Batman and Robin, appeared in a one page comic strip ad featured in many of DC’s comics about “Sportsmanship” and the un-American practice of excluding people because of race and religion.

In Will Eisner’s groundbreaking and wildly popular newspaper comic strip, The Spirit, Eisner introduced Lieutenant Grey, a black non-comedic supporting character. Soon thereafter by 1949, Eisner phased out the Spirit’s minstrel-influenced sidekick, Ebony White. Perhaps the most poignant statement of anti-racism in comics from this era came from publisher, EC Comics.

In 1953’s Weird Fantasy # 18, a story entitled “Judgement Day” pushed the comic medium to new heights with its hopeful futuristic anti-racism story created by writer Al Feldstein and artist, Joe Orlando. The story concluded with a black astronaut determining that the planet he had visited was unfit to be admitted into the Galactic Republic because the planet’s population of blue and orange robots were treated differently based on their outer color. When the story was reprinted during the early years of the Comics Code Authority in 1956, publisher Bill Gaines quite comics in protest to the racial censorship by CCA administrator, Judge Charles Murphy.

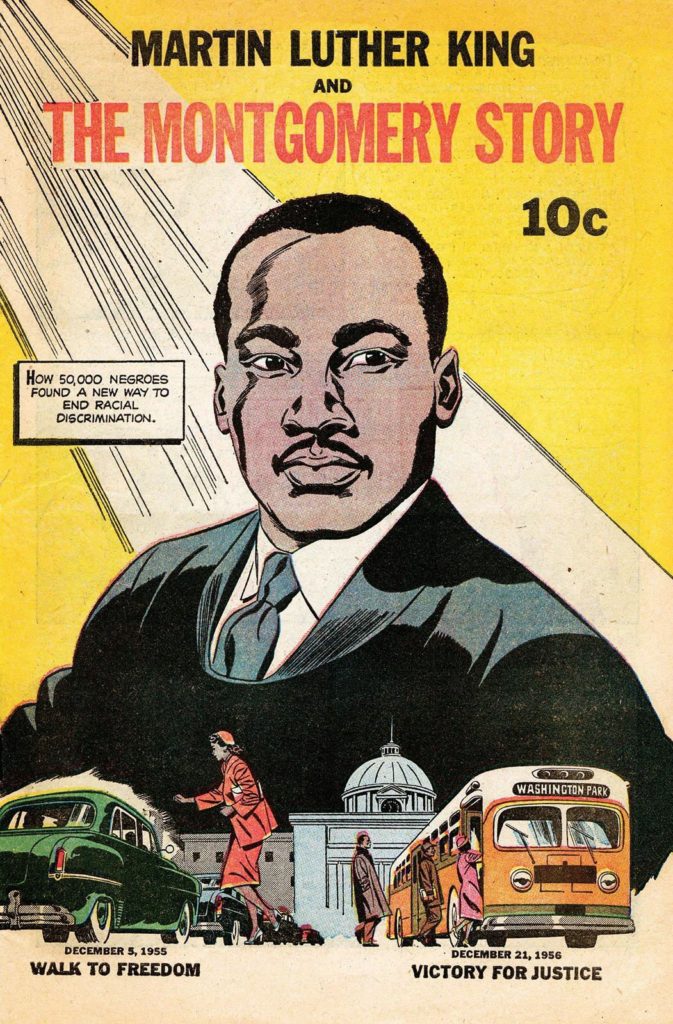

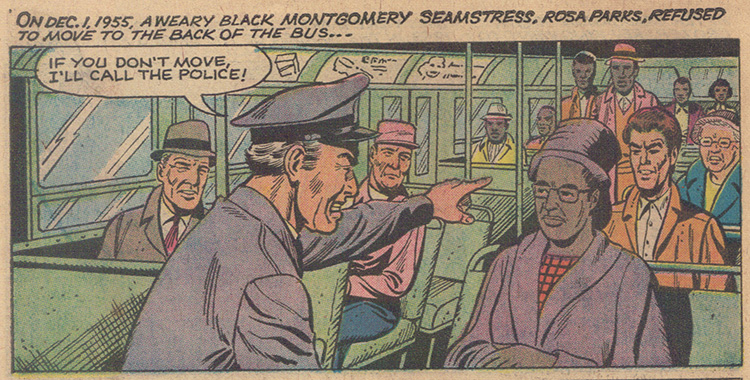

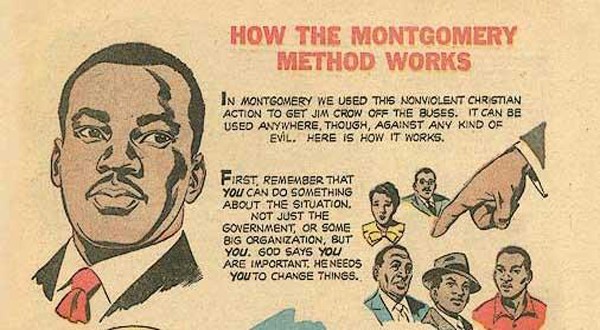

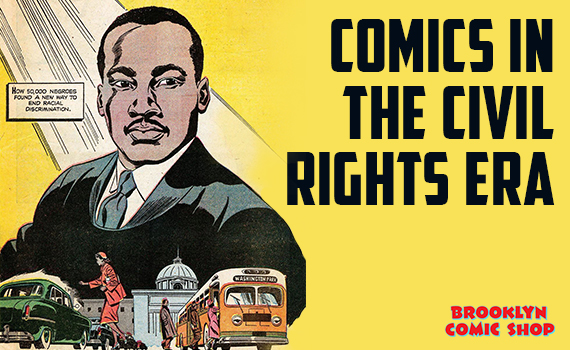

Although not to be found on any newsstand, the most explicitly direct promotion of Civil Rights during the 1950’s came from the Al Capp Studio. Al Capp was the creator of the widely popular, Lil’ Abner syndicated newspaper cartoon strip. In 1957, Al Capp’s art studio “Toby Press” created and published “Martin Luther King and the The Montgomery Story” a comic book that featured Dr. Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks. The story was written by Benton Resnick and illustrated by Sy Barry. The comic was, by most accounts, distributed for free by peace organizations during workshops and speaking events despite its ten cent cover price. The comic book had an edition size of 250,000 copies.

“Martin Luther King and the The Montgomery Story” opens with a one-page synopsis of Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and education up until current time (1957), as well as a description of life in Montgomery, Alabama, which at the time of publication was still under Jim Crow laws. The comic book continues to recount the Montgomery bus boycott and featured Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr.’s roles in the event. At the close of the comic, the reader is reminded of Martin Luther King Jr.’s commitment to non-violence and advice on how to act appropriately to advocate for change.

Many of the writers, comic creators and publishers at DC Comics, Marvel Comics, EC Comics and Archie Comics and more were Jewish. Because of their Judaism (wether observant or not) they were sensitive to racism in America. Many of them had their own experiences with anti-Jewish hate, blacklisting, and Pogroms both in the United States and in the countries from which their families emigrated. You can see these undertones reflected in both the DC Superman and Batman ads when they mention religion and immigration. Many of these Jewish creators were first generation Americans, and loved America for the freedoms that their parents were denied in Eastern Europe. In fact, American Jews saw the Civil Rights movement as an extension of the fight against anti-Semitism.

After all, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) was founded in 1913 because of the blatantly false accusation and anti-Semitic show trial of Leo Frank. Frank had been a young prominent Jew and president of the Atlanta chapter of the Jewish organization, B’nai Brith. Frank was later kidnapped from jail and lynched in Atlanta, Georgia. The Ku Klux Klan used the event as a way to “re-brand” itself to oppose Jews, Catholics, and immigrants, alongside Blacks.

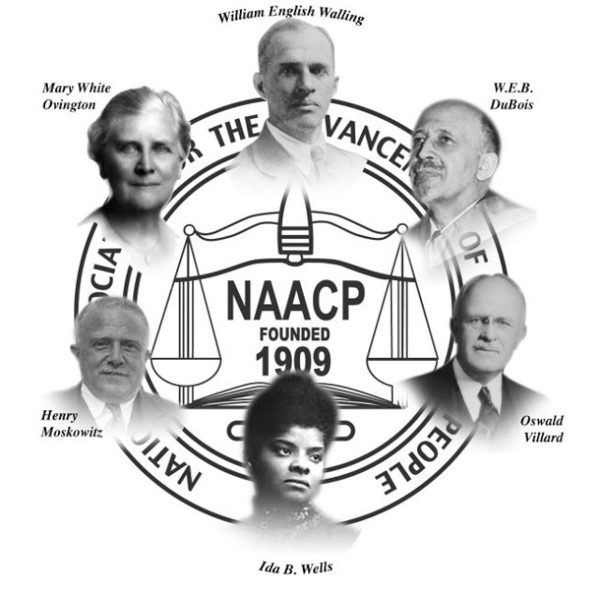

Even earlier than this was the formation of the NAACP in 1909, whose founding members included Henry Moskowitz. Moskowitz was an activist for equal rights for blacks. He was also a defender for the plight of Jews in Europe in the pre-Nazi era.

As we remember Black History Month this year, let us reach beyond the entertaining comic-fiction mythology that we love so much, and instead towards an exploration of a more meaningful look at how the comic industry helped shape real change in America.

Joshua H. Stulman

Owner, Brooklyn Comic Shop

Leave a reply